They say you can’t teach an old dog new tricks, but that’s not true. If you take advantage of Pavlovian conditioning, you can train anyone–dog or user–to behave in a certain way. Here’s a brief guide to using Pavlovian Conditioning in UX design.

This post is part of a 9-part series on UX psychology. Read the next post on mental models.

What Is Pavlovian Conditioning?

Pavlovian Conditioning all started with a physiologist named Ivan Pavlov, who was researching dog salivation rates. The dogs would always salivate when fed. However, Pavlov soon noticed that the dogs would start drooling whenever a researcher opened the door.

After some experimentation, he realized that the dogs had been conditioned to associate door-opening with tasty treats. As a result, they would drool every time the door was opened–even if there weren’t any scrumptious snacks awaiting them.

So What?

We love dogs, but they can’t use apps (for now). However, Pavlovian conditioning works on humans, too. If you build an association between a stimulus and an event, the user will subconsciously link the two. In the same way that you can train a dog to sit by giving it treats, you can train a user with Pavlovian conditioning.

However, that’s not as easy as it sounds. Make sure you condition correctly.

Give Feedback

When a dog does a trick, you give it a treat or a chin scratch. In other words, you condition the dog by giving it positive feedback.

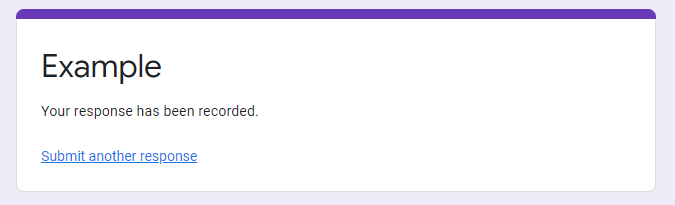

That’s true for users, too. You give them feedback when they complete an action.

However, feedback doesn’t need to be so obvious. Some of the most important feedback is subtler–like the micro animation.

A micro animation is a tiny bit of motion that livens up your UX elements–if you haven’t read our article on micro animations yet, it does a great job explaining what makes micro animations so great. They are especially useful for giving users feedback.

For example, hovering over a button on our website makes it change color and size.

This teensy-tiny animation gives the user just enough feedback to feel good about clicking the button. Don’t believe us? Here’s the same button without micro animations.

It looks a lot clunkier now. Just a bit of movement made all the difference.

When you give the user feedback, you reinforce their actions. As a result, they will want to use your app more.

Build Associations

Users won’t like your app right away. You have to teach them how to like it.

The best way to do that is through pavlovian conditioning. Associate an action with a positive result. That way, the user will learn to enjoy the action–even if the positive stimulus goes away. After all, that’s why Amazon ships your packages so fast. It’s not to make more money–Amazon lost money on one-day shipping. In actuality, Amazon only wants to ship your package in one day so you more strongly associate the purchase with the item.

Think about it: back in the ancient pre-amazon dark ages, you’d have to wait upwards of a week for a package to arrive. Once it got there, you may have forgotten purchasing it.

On the other hand, your heavily-branded amazon package arrives lickety-split, which more closely associates the package with the app.

While this conditioning isn’t entirely in-app, it still makes users like the app more. Users build an association between a neutral action–using the app–and a positive result–getting the package. Overall, that conditioning makes the app seem better.

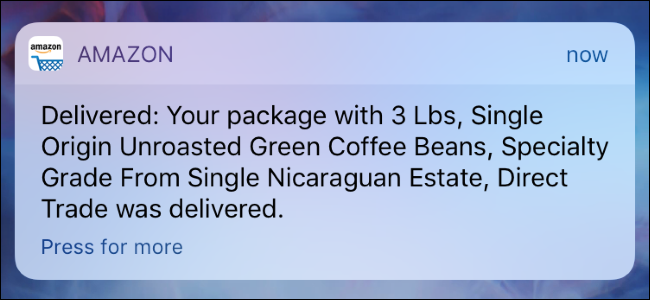

Send Strategic Notifications

Speaking of the Amazon app, it’s full of pavlovian conditioning. Most notably, Amazon conditions you to associate its app with package delivery. When you get a notification that your package has arrived, you subconsciously link the notification with receiving a package.

After a while, Amazon can subconsciously get you excited by sending any notification–with or without a package.

Condition Against Bad Actions

So far, we’ve talked about how to use Pavlov to make actions seem better. The reverse is true, too: you can disincentivize certain actions by removing feedback.

This reverse-pavloving strategy was key to the video game Subnautica. The game developers wanted players to explore an alien ocean without trying to kill all the creatures. However, they didn’t want to make creatures unkillable–that would just be unrealistic. The developers came to an elegant solution: when a creature is killed, it stops moving and floats lifelessly without any extra animations, loot, or points.

This strategy is brilliant. Instead of robbing the player of their freedom and the game of its realism, the developers removed feedback. As a result, users are not positively-conditioned to kill creatures like they are in other games.

Pavlovian conditioning may be simple, but it can be very powerful if you use it correctly. Do remember that it isn’t the only psychological phenomenon to worry about. We’ve written an article about the eight most important psychological principles in UX design. Make sure you check it out before designing new user experiences and let us know what you think.

Donovan Reeves

Donovan Reeves